By TastyGherkin, August 29, 2018

Gaming communities often use the terms "skill ceiling" and "skill floor", particularly in team-based games and card games. However, the idea of skill ceilings and floors remains largely unexplored in the context of Gwent.

Gwent's Skill Ceilings and Floors: Three Deck Specific Skills

To understand the terms better, we must first define them. Furthermore, while the terms can be applied to various aspects of Gwent, such as different factions or mechanics, or even Gwent as a whole, this article will focus on how three key skill types apply to the skill ceilings and skill floors of every Gwent decks.

Skill Ceiling

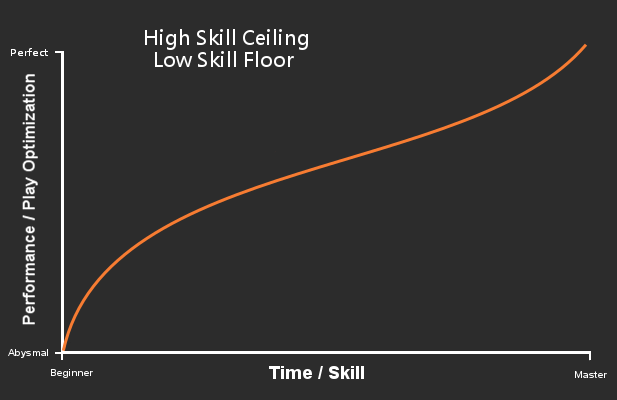

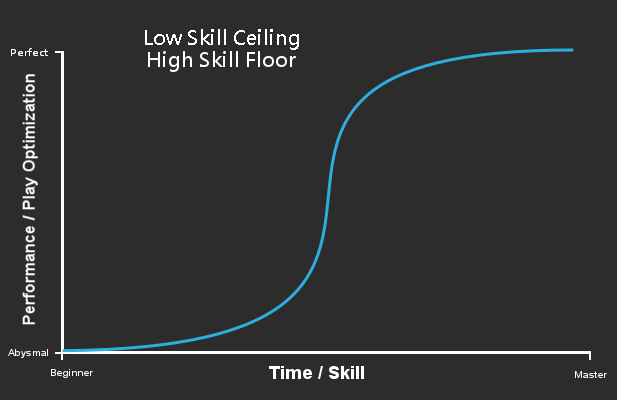

"Skill ceiling" (also called skill cap) refers to how much the performance of a deck can improve as player skill and experience increases. A deck with a high skill ceiling means the deck is difficult to play optimally and rewards higher player skill. A deck with a low skill ceiling means that the deck’s optimal line of play is easy to achieve, even with low player skill.

Skill Floor

"Skill floor" refers to how easy it is for a new or inexperienced player to pick up the deck and play it at a competent, but not necessarily skilled, level. A deck with a high skill floor is difficult for new or inexperienced players to understand. A deck with a low skill floor is easy for a new player to pick up and win with; a “beginner’s deck.”

Ceiling, Floor, and Power Level

Skill ceiling and skill floor—hereafter, "ceiling" and "floor"—are not necessarily mutually exclusive. A deck can have both a low floor and high ceiling (“easy to learn, hard to master”), or a high floor and low ceiling (hard to learn and little improvement after).

Ideally, all decks would have a low floor and a high ceiling. Having a high floor only raises the barrier of entry for new players while having little impact on experienced players. Likewise, having a high ceiling for all decks is almost always desirable, as it makes skill an increasingly important factor for winning over luck.

Additionally, ceiling and floor do not necessarily correlate with deck power level. Decks can be easy to play and still be extremely strong, or else difficult to play and weak at best.

Skills Gwent Decks Require

To understand what makes a deck have a high or low ceiling or floor, we must examine the skills Gwent tests when playing a deck. Skills can either be general or specific to a deck. General skills do not depend on the deck you are playing. These include knowing the metagame, knowing what matchup you’re facing, and knowing what cards your opponent may have in their hand based on their plays. These skills are largely transferable from deck to deck.

Because of general skills, ceilings are never absolute. There will always be some way to improve your plays, no matter how small, even with the simplest of decks. However, most of the optimization for decks with low ceilings will come from general skills. Over-analyzing specific plays in a low-ceiling deck will yield only marginal improvement in performance.

Regardless, specific skills are focus of this article. There are three main deck-specific skills in Gwent: mulliganing, sequencing, and passing. These categories have some overlap with each other and general skills.

Mulliganing

Mulliganing allows you to replace a card in your hand with a card from your deck. You can mulligan up to three cards at the start of Round 1 and up to one card at the start of Rounds 2 and 3. The mulligan phase also includes a feature called blacklisting, where you will not draw any copies of a card that you have already mulliganed away.

Mulliganing tests your skills in getting the best draw possible for your deck, minimizing drawing low-value cards ("bricks"), and drawing important cards for a specific matchup. Mulliganing is a test in probability and risk/reward management. Skilled players will be rewarded over the long run for maximising their chances of getting a good draw.

The complexity of mulliganing is deck-specific and centres on how many "bricks" are present. Decks generally fall into a spectrum from brick-light to brick-heavy. Decks which are brick-light or do not make heavy use of the blacklisting feature, such as Brouver Shupe or Crach Veterans, generally do not demand a high level of mulliganing skill. They have a low mulligan ceiling and floor.

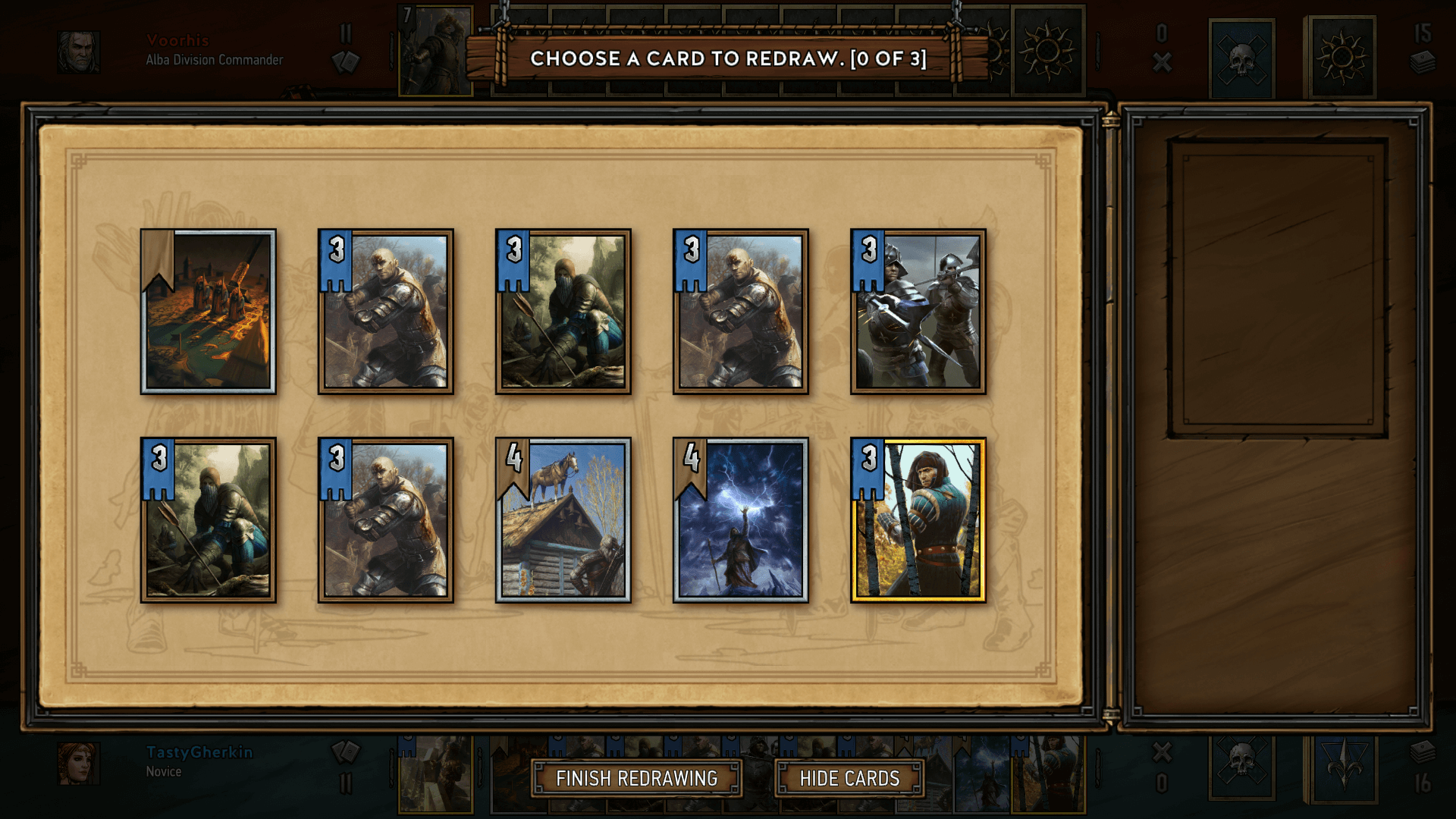

Veterans generally has a straightfoward mulligan

Brick-heavy decks can have a large amount of variance in the difficulty of their mulligans. If the initial draw only contains a few bricks, mulliganing can be trivial, as there is no decision-making involved; simply mulligan and blacklist away the few bricks. For example, many King Foltest decks run cards such as Blue Stripe Commando and Temerian Infantry. You seldom want to keep these cards in your hand, so it is an easy decision to mulligan them away. These situations often require little skill other than basic use of blacklisting.

However, if an initial draw contains many bricks, mulliganing becomes complicated. In a similar situation with a Foltest deck, imagine a draw with three copies of Temerian Infantry, two copies of Blue Stripe Commando, and Roach. As there are more bricks than mulligans available, suddenly the mulligan requires decision-making on what to prioritize for mulliganing. In this example, the correct mulligans will depend on many factors, such as access to gold cards to pull Roach and how many Blue Stripe Scouts are in hand.

An example of a complex mulligan. What is the correct mulligan in this situation?

Another example of a brick-heavy deck is Calveit Alchemy. A large number of bricks within Alchemy leads to many counter-intuitive decisions. For example, it is generally a good idea for Alchemy players to keep one or two Ointments in hand, despite them being bricks during Round 1. This is done to prevent Vicovaro Novices from drawing two Ointments or the very small chance Jan Calveit pulls three Ointments. This trade-off requires some decision-making; while keeping Ointments in your hand prevents these bad situations, it also does not make full use of the blacklisting system to draw high-value cards and denies the Alchemy player the option to push Round 1 harder, which may force them to pass in an unfavourable situation.

These high-variance situations provide the greatest challenge for players and offer the highest ceiling for mulliganing.

The dreaded three Ointments from Calveit in Gwent Open 6

Sequencing

Sequencing is the order of playing your cards in Gwent. The skill in sequencing comes from playing your cards in the order that generates the most value, either by increasing your own points as much as possible or by preventing your opponent from doing the same.

Depending on the deck, sequencing can either be trivial or non-trivial. For example, with decks that make large use of immediate high-value bronzes such as Half-Elf Hunter or Tuirseach Bearmaster (sometimes known as “point-slam”), the order of play is less important and does not demand a high level of skill. These cards provide the same value of points regardless of when in a round they are played in most situations. This gives them both a low floor and low ceiling.

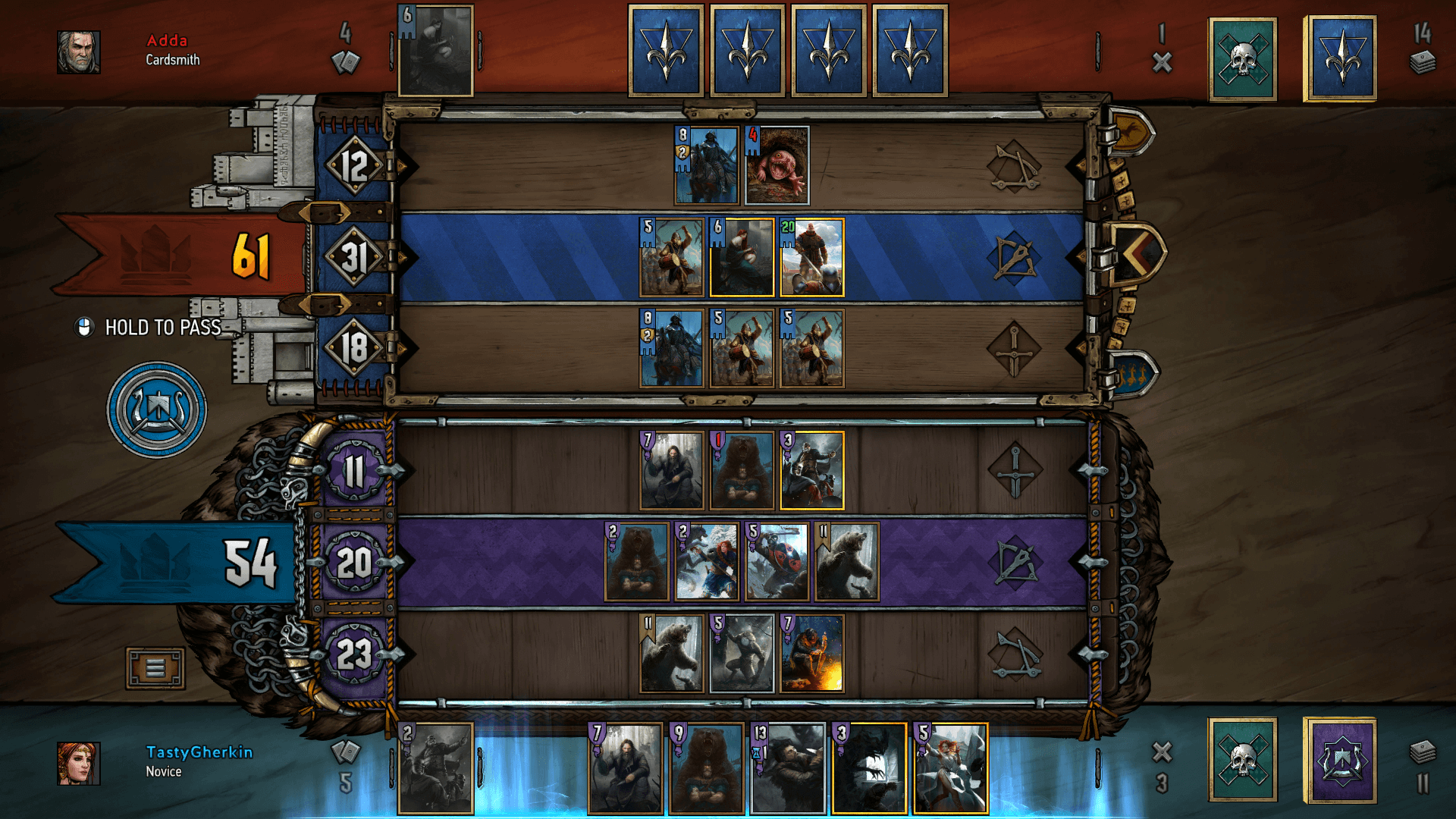

Veterans have little depth to sequencing; their order of play varies little in most games

In contrast, certain cards require difficult sequencing to get the most value out of them. The most straightforward examples are "engine cards," cards that generate value over time. These cards are vulnerable to removal, so playing them early, which would normally generate the most value, may not be the best choice available. You may have to attempt to bait out your opponent’s removal by playing less important engines or bluff not having any engines, making sequencing difficult. The reverse is true for deciding when to use removal.

Weather and weather clears present a similar conundrum. Decks that make heavy use of engines, such as Harald Axemen or Bran Boats, are very difficult to find the optimal sequence value for and generally are inaccessible to new players. This gives them high sequencing ceilings and floors.

There are also less obvious ways sequencing can be important. Thinning and avoiding bricks may be difficult to sequence correctly. This can range from the simple, such as playing a gold card to pull Roach before using other summoning effects such as Prince Stennis, to the more complicated, such as deliberately playing suboptimally to kill off your own units to enable resurrections, as is important in many Skellige decks.

Sequencing also includes risk/reward management, as with the mulligan stage. For example, do you attempt a low-tempo thinning play early or make a high-tempo play first? The latter risks drawing a brick, but with the potential reward of out-tempoing your opponent to either gain card advantage or give yourself breathing room to play a low tempo engine.

Some decks have both a low floor and high ceiling in sequencing, such as Calveit Alchemy. As the deck is centred around high-value individual plays, such as its fifteen-point Viper Witchers and fourteen-point Vicovaro Novices with Mahakam Ale, it is a largely accessible deck to new or inexperienced players. These core cards do not require a huge amount of skill to get acceptable value out of, thus giving Calveit Alchemy a low floor. However, the deck also rewards higher-skilled players, as it has many ways to optimise sequencing, such as thinning correctly with Vicovaro Novices, using Assire var Anahid on the correct targets, or knowing when to save your Viper Witchers to hit important targets. This gives it a high ceiling.

shinmiri2 explaining an advanced sequencing technique for Alchemy

Positioning

Positioning is partly a subset of sequencing, as most positioning occurs while optimizing sequencing. However, the majority of positioning is both trivial and a general skill, such as avoiding Geralt: Igni or Expired Ale. While there is some deck-based positioning, particularly in weather decks such as Harald Axemen or Eredin Frost variants, most positioning is general, placing it beyond the focus of this article.

Passing

Finding an ideal time to pass requires setting up a pass that is advantageous to you and disadvantageous to your opponent. Passing is arguably an extension of sequencing, but while they are related, passing is distinct enough to be considered its own skill. This skill is somewhat transferable from deck to deck, but as different decks want different outcomes from a pass, passing strategy will vary.

The most straightforward way to pass advantageously is passing in a situation that will give you “card advantage,” putting yourself in a situation in which you have more cards in hand than your opponent. The most common way of doing this is winning Round 1 on even cards or losing Round 1 two cards up. This is more easily achieved on red coin (going second).

In order to gain card advantage this way, you must "out-tempo" your opponent by playing more points than your opponent in a short amount of time, generating enough points that your opponent cannot catch up in a single card. Knowing how much tempo your deck can generate in relation to your opponent’s deck is crucial. Consequently, decks that rely on gaining (or at least not giving away) card advantage generally require a strong understanding of when to pass to maximise their effectiveness, giving them a high passing ceiling. This includes decks that rely on strong finishers and prefer short rounds, such as Calveit Alchemy or Crach Veterans. Cards that tend not to care about card advantage, such as Nekkers Consume, do not, which gives them a low passing ceiling.

Winning Round 1 with the same amount of cards as your opponent is the most common way to gain card advantage

Another way passing can be advantageous is baiting engine cards out of your opponent early. If your opponent plays or you bait out many engines, including weather, it may be advantageous to pass before your opponent can gain value out of them. However, passing early gives round length control to your opponent, which may be costly if your opponent has additional engines. Like decks that prefer short rounds, decks that prefer long rounds also require finesse in passing, giving them a high ceiling in passing. Strong preference for either extreme of round length gives both a high ceiling and floor to passing.

Passing is also tested as a skill through "bleeding" your opponent, though this is strongly related to sequencing. Bleeding occurs in Round 2 where the player who won Round 1 forces the opposing player to continue to play cards ("bleeding" their cards), as they cannot afford to pass. Bleeding is generally a good idea if you know most your cards are weaker than your opponent's or wish to force your opponent to play an important card, such as Shupe's Day Off. Similarly, if you find yourself being bled in Round 2, your goal is to commit the least amount of points possible to Round 2 to save your best cards for Round 3. Therefore, decks that are more vulnerable to being bled have higher ceilings.

The Skills Together

Different decks will have different floors and ceilings for each of the three main skills. For example, a deck might have a low ceiling in mulliganing but a high ceiling in sequencing. Looking at these three skills individually allows for some level of value judgment for the deck's overall floor and ceiling.

Conclusion

This exploration of floors and ceilings is not meant to be a complete analysis of the floor and ceiling of every popular Gwent deck, but rather a starting point in how to analyze and look critically at what skills Gwent decks demand of their players, and use this knowledge to hone their skills.

My thanks to Danman223 and lordgort for their valuable feedback and editing.

Author