The Triangle Concept Pt 1: Triangle Theory

From the name, we can already take away that there are three elements to the Triangle Concept, and before we look at how the concept is used in Gwent, we should first understand what these elements are and how they interact with one another. This is what we will cover in Part 1 of this series: Triangle Theory.

Elements of the Triangle

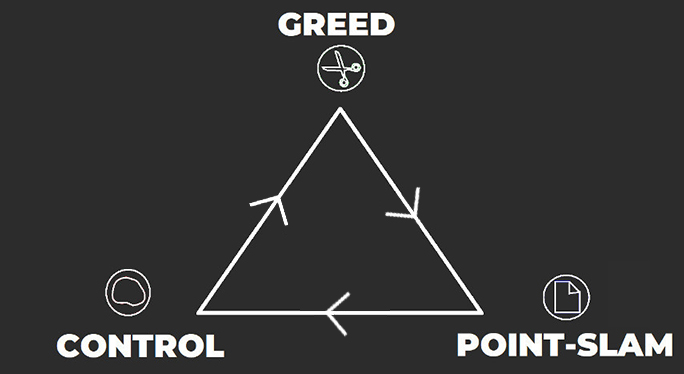

The elements of Triangle theory are all concepts in and of themselves: They describe how decks, card packages or even individual cards work at a very basic level. These concepts are greed, control and point-slam.

Greed

If you are familiar with other card games that use mana systems and the concept of player health, you may be familiar with the term “aggro”. This is the concept of reducing your opponent’s health as quickly as possible, usually using low-mana-cost cards. The idea is to focus on this goal and not to interact with what the opponent is doing. By the time they are in a position to respond to your level of aggression (from which aggro comes), they are so far behind that it becomes impossible for them to win.

Of course, Gwent has no mana, or player health. This means aggro itself cannot exist. However, Gwent has a concept that works very similarly, and that is “greed”. Implementing this concept still means focusing on your gameplan and giving up the opportunity to interact with your opponent's pieces, but instead of looking to reduce the opponent’s health, you look to generate more points than them, without doing as much to interact with the opponent’s side of the board.

Simply because the concept focuses on a lot of points, though, doesn’t mean the points come quickly. Greed often means the use of engine cards that are played early for little immediate value, but keep adding to your total score over the course of a round or game. Greed can be devastating when left to run rampant, but the concept is as fragile as it is powerful; if countered, be it by an opponent or bad RNG, you can be left with nothing to show for your avarice.

Control

The concept of “control” is incredibly popular and deeply polarising inside the card-gaming community. If you have played any CCG for any length of time, you have probably experienced a game in which no matter what you do, no matter how many cards you play, your opponent always has an answer. You try to execute your game plan - they will play card after card to make sure your game plan fails. You manage to set up a board state where you are certain that victory is yours and with a single card your opponent completely turns the game around. Cancel in Magic: The Gathering, Silence in Hearthstone, Annihilation in Artifact, Scorch in Gwent. This is control: The ability to answer your opponent’s threats, deny their game plan and strike back when they’ve exhausted every resource.

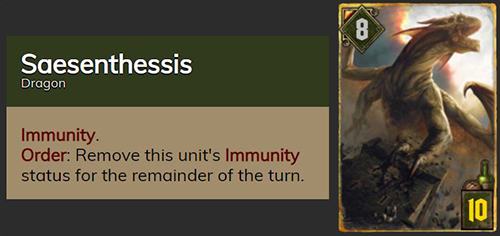

By its very nature, control is slow and drawn out. In Gwent, an extreme example of the concept might mean playing very few, if any, points on your side of the board until the very end of a game. Focus first on minimising the amount of value your opponent can generate, achieving this through a number of means. Control does not just mean removal; mechanics like Lock and Seize can also be effective in stopping engines and deck disruption abilities such as that of Infiltrator, Traheaern var Vdyffir and Assire var Anahid can simply stop your opponent from getting that key card when they need it.

Point-slam

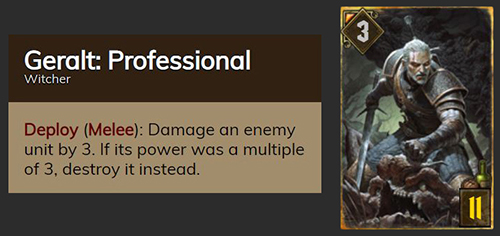

“Point-slam” exists purely because of Gwent’s fundamental design. The game revolves around the points a deck can generate, and so immediate impact that cannot be stopped is a high-value commodity. This is point-slam. While greed generates immense value over time at the risk of being shut down, point-slam finds immediate value at the cost of long-term relevance. Point-slam cards, often but not always units, are played, affect the point total and make little or no further contribution to the game after that immediate effect.

The term first came into wider circulation after the Midwinter Update of Gwent's open beta, with Bear SK and Gnurrgard’s infamous SK Veterans deck both receiving not-insignificant scorn at the time due to what was seen as a simplistic play-style for very strong results. The simple truth, however, is that point-slam is perhaps the most key concept to understand about Gwent. A game cannot be won without playing points, and slamming those points down quickly is perhaps the most efficient way to do so.

The Basics of the Triangle Concept

Now that we understand the greed, control and point-slam, we can look at how they interact with each other to form the basic premise of Gwent’s Triangle Concept.

Most of us know the most basic form of the Triangle Concept. Rock beats scissors, scissors beats paper and paper beats rock. If we assign one of our card-gaming concepts to each of these three objects, we start to get a basic idea of their interactions.

This is the fundamental rule upon which we can build our understanding of the Triangle Concept. It is very simplistic, but particularly important for understanding why it becomes more complex. Additionally, by replacing greed with aggro and point-slam with midrange (a term used liberally in Gwent, as we’ll explore in the next article), you have a good fundamental rule not just for Gwent, but for the entire CCG genre.

So to round off Part 1 of this series, let’s take a quick look at why the concepts are arranged in this manner.

What do we know about greed? Often, it relies on generating points over time, which means playing engines early to start snowballing. In some circumstances, the concept requires a big, powerful finisher, but in any case, all of the value is poured into a small number of units that each have a lot of card-strength, creating what is called a “tall” board. What happens if these engines are stopped before they can generate this value? What happens if these big units are simply removed? This is why control beats greed; it plays into the binary nature of greed, shutting down each tool with its own until greed has nothing. Additionally, it takes great advantage of greed’s lack of interaction with its opponents, meaning control can use its own tools effectively without disruption. Rock beats scissors.

So why does greed beat point-slam? Simply: Point output. At the beginning of a round, point-slam may outvalue greed while greed sets up its engines, but as the round goes on, the more value greed generates. Over time, it catches up and overtakes point-slam with ease. Surely this means that point-slam must keep rounds short? In theory, yes, but keeping the round short potentially means a voluntary pass, which gives greed control of the next round. It can simply use that opportunity to set up its engines instead, leading to an inevitable point ceiling that point-slam simply cannot contend with. Scissors beats paper.

Finally, we look at how point-slam beats control. This might seem counter-intuitive: If control is effective at removing the value of greedy decks, why can it not also handle the smaller point output of point-slam? The answer lies in how control handles greed. There are lots of different types of control, but many are far more effective at stopping value generated over time than they are at stopping immediate value. The only way of dealing with immediate value is to remove it again, and when you are limited to removal, your control options become far more limited. Unlike greed, which “goes tall”, point-slam tends to “go wide” - that is spreading its value over far more units. Area-of-effect cards can be quite effective against this, but single-unit removal options lose a lot of value, and it becomes easy for well-played point-slam to make sure AoE effects reach limited value too. After that, as with greed over point-slam, point-slam has a higher point-ceiling than control, and uses that to win the game. Paper beats rock.

Conclusion

With this article, we have come some way to understanding the different battling fundamental concepts that make up games of Gwent, and started to look at how these concepts interact with each other at a very basic level.

In the next article in this series, we will look at how these concepts are actually applied in Gwent and how that differs to other CCGs as well as taking a quick look at how Triangle Theory has evolved in Gwent over time.

Author

Lothari

Lothari is a long-time fan of CCGs, building up a wealth of experience in Hearthstone, MTG, TESL, Artifact and of course Gwent, which she has been playing since the end of Closed Beta. She always aspires to improve and learn more about what has come to be one of her favourite pass-times. She has also found a passion in creating content for Gwent, and will continue to do so with a passionate and analytical outlook for Team Aretuza. Lothari has a BA in Computing and German and spent four years working as a game developer.