By Lothari, May 3, 2019

In the first part of our series on the Triangle Concept, we looked at the three basic elements of Gwent's triangle and how they interact with each other. Greed beats point-slam because of its much higher point output, point-slam beats control due to control’s limited reach against point-slam’s immediate value and control beats greed because it is able to interact with and shut down important elements of a greedy strategy before it can start to snowball. Now that we know this, we can start to explore how the Triangle Concept is actually applied in Gwent, and this is what we will set out to do in Part 2 of the series, Triangle Application.

The Triangle Concept Pt 2: Triangle Application

Other Application Examples

In order to understand how the Gwent we know applies the Triangle Concept, we must first look at where we’ve come from. Importantly, this means looking at how other games in the same genre as Gwent apply the same theory.

In any card game, a constructed deck is a collection of carefully selected cards that sets out to achieve a certain goal in a certain way. In many CCGs, a deck’s archetype describes how it goes about achieving its goal - an idea that uses a certain mechanic or synergy to reach its win condition, using most of or even every card slot in the deck to work towards this goal or support it in some way. An archetype’s win condition is then defined by its deck type - the fundamental goal any deck tries to achieve.

This is how the Triangle Concept has historically been applied in CCGs. In those that use health and mana systems, aggro, control and midrange (a term used quite differently in Gwent) are the principle deck types upon which any deck is built, regardless of its archetype. In Hearthstone, Renolock and Burn Mage were very different archetypes, but their ultimate goal was still to run the opponent out of resources before making their own move; they were both control decks. In Magic: The Gathering, RDW and White Weenie are both aggro decks, though one focuses on cheap creatures while the other focuses on spells looking to damage the opponent directly.

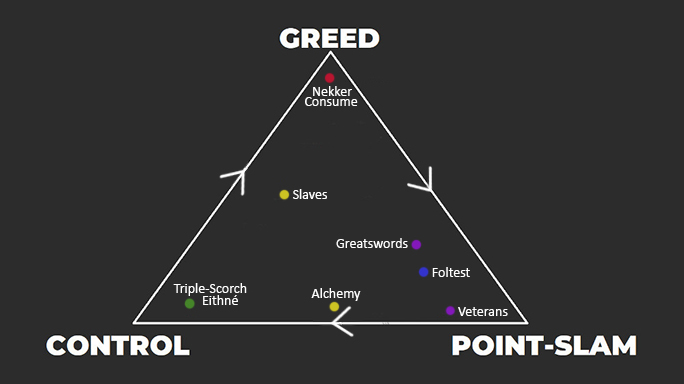

In the past, Gwent has also worked this way. Gwent decks too had an archetypal structure with the ultimate goal of beating your opponent through greed, control or point-slam, or a fusion of two of these. Those of us who played in Gwent’s open beta remember well decks like Nekker Consume - a deck capable of generating hundreds of points in Round 3 if left to snowball, Triple or Quad-Scorch Eithné - a deck that would punish any deck that didn't carefully stagger its points to avoid both tall and wide removal, and as mentioned in Part 1 of this series: Veterans - a bombardment of point-slam plays that took advantage of Gwent’s round-based structure to invest immediate value in your future rounds where it could not be as easily countered. Many if not all of Gwent’s open beta decks followed this archetypal pattern that focused almost everything on a single win condition.

This deck type triangle uses decks from Gwent’s open beta. It is not indicative of the current state of the game.

Card Packages and the Triangle Concept

It is in these card packages that we find Gwent’s ‘modern’ implementation of the Triangle Concept. Instead of a deck having a particular type as described above, or even a fusion of types that was still possible to achieve under the previous design (NG Alchemy was a perfect example of a point-slam/control fusion), we see decks including packages of a certain type, which are then fitted together like a jigsaw puzzle to give us the overall picture. It is true that a deck may run so many packages of a single type that it looks and plays similarly to an old archetypal deck, but a key difference between then and now is that now decks are far more likely to contain cards belonging to a different type, even an opposing type, in order to make it stronger.

Let’s take a look at a clear deck example to see what this entails:

Big Monsters is often referred to as a point-slam deck, and while it might be true that its finisher, often a combination of Old Speartip, Old Speartip: Asleep and Count Caldwell either from hand or replayed from the graveyard with Ozzrel, is a point-slam package, on closer examination of the deck, we can see that a lot of the deck heavily incorporates both greed and control.

If we look first for examples of control, we see Imlerith's Wrath taking advantage of the tall point-slam creatures the deck contains to also include tall removal, while Gimpy Gerwin can act as a tremendous wide removal play on many 3-point engines. Cyclops, in combination with many cards in the deck, but primarily Foglet, is a great control option, and even Plumard keeps the number of points on the opponent’s board more manageable as a form of control.

The Thrive package included in the deck, Nekker Warrior, Wyvern, Alpha Werewolf and Katakan is the definition of greed, played early in a given round and gaining ever more value as you play higher- and higher-strength units. It is these cards that help Big Monsters stay in a longer round when you do not yet want to commit the stronger point-slam plays.

Continuing our observations, we also see the Crones value package, with Brewess often acting as a greedy Consume proc, Whispess representing control and Weavess used as pure point-slam. This example perhaps shows best how Gwent is now designed: The three cards work better together than separately; they synergise, in fact so well that it doesn’t make sense at all to run one without running the other two, but in doing so any deck that runs the entire package breaks away from the corner of Gwent’s modern day deck type triangle and towards its centre. Big Monsters is not a point-slam deck. It has a point-slam finisher, and the archetype - if it can even be called a traditional archetype - now incorporates the name of this finisher to make it the deck highlight, but the deck type itself is a fusion of all three of our triangle concepts.

This in and of itself can perhaps show us how to build better decks in Gwent; a more extreme example of what we already began to see at the end of the open beta. A deck that focuses itself in one corner of the triangle is strong against its opposing corner (point-slam beats control). If the same deck shifts the cards it uses to sit on the edge of the triangle, it might find itself performing slightly better against decks it should be weak against (a point-slam deck incorporating control could beat a greedy deck). If it then pushes itself towards the centre of the triangle (Big Monsters), it might find the strength it needs to be classed as a bone fide tier 1, or even tier 0, deck.

Of course the deck-building mechanics that Gwent employs stops us from taking this too far. A maximum provision cost, and the ever-present balancing act of requiring as few cards as possible in your deck to make it as efficient as possible, means that we are never likely to find a deck that reaches the very centre of the triangle, there simply isn't enough space. With those limited resources, you also can't afford to overstretch - if you take away too many cards from your finisher package to add more support in other areas in an attempt to make the deck better, you might accidentally end up making it worse. In the end, it is a balancing act, to find the combination of packages that works best with the cards available, and in a well-balanced game, it is a puzzle that creates a number, a small number, of different solutions.

Triangle Concept Homogenisation

Importantly, Big Monsters also highlights how the Triangle Concept has been applied to the design of even individual cards. When you look at the mechanics of Protofleder, Whispess and Wyvern and more, it is clear to see. That said, we will look at an even simpler example moving forward.

Card screenshots from The Voice of Gwent.

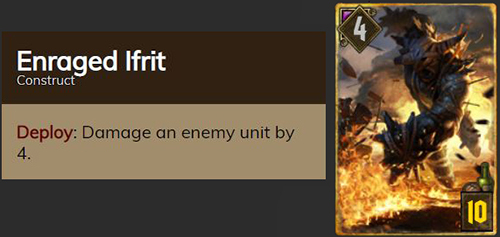

What does Enraged Ifrit represent? It is a unit, a body on the board and 4 points of immediate value for you. However, the real value of the card comes with the 4 damage that can be done to an opponent’s unit. As a Deploy effect, this is also immediate, and helps tie into the card’s point-slam nature, but as a damage effect, in a worst case scenario you manage to remove 4 points of value from your opponent, and in the best case scenario, you remove a key engine before it has the chance to snowball. As well as representing point-slam, Enraged Ifrit represents control.

In open beta Gwent, there was one prime example of this kind of card; Viper Witcher, and not only was the entire archetype built around this card, but it was arguably the reason why the archetype was - at its worst - one of the strongest high tier 2 decks available. Now, Gwent has been overwhelmed with these concept-fusion cards, and it has dramatically changed how the game is played. The sheer number of cards, particularly Neutral cards, that can add to a player’s point total while dealing damage has made it difficult for truly greedy decks to find a good footing in the game. Engines are incredibly targetable, and players have quickly learned that they must usually sacrifice one in order to better ensure another might live.

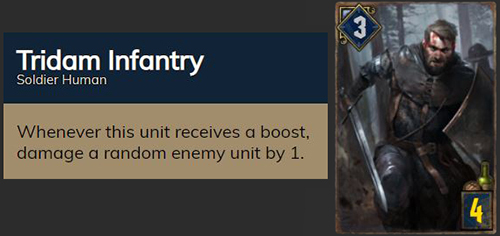

While point-slam/control fusion cards are perhaps the most prominent fusion cards in the game, they are not the only one. Greed/control cards are also available, doing damage to the opponent on a rechargeable Order or as an ongoing effect. Northern Realms particularly has many of these control engines. They are greedy in that if left to snowball, they will find tremendous value, but they are not traditionally greedy, as the value is taken away from your opponent, instead of given to you. Once again, their worst-case proccing scenario is to manage the number of points your opponent can achieve, but if you are lucky, you might shut down a key engine or two while you're at it.

Rarer, but still available, are point-slam/greed fusions. These are cards such as Mourntart and Glustyworp - when they are played, they have an immediate point-slam impact, but the round-long or even game-long set up required for them to reach full value, often much higher than their truly point-slam counterparts, makes them far greedier than average. Of course, the greedy nature of this fusion is tremendously vulnerable to control, but the point-slam element can help draw some of the lost value back. While round-long or game-long set up makes these cards incredibly effective, they can still be effective with minimal set-up which, if you don’t fall foul of telegraphing, allows you to play more around control than with truly greedy cards.

These fusion cards have become the life-blood of Gwent, making the monthly balancing patches we now see more important than ever before to make sure we don’t see a meta where one of our three basic game concepts are drowned out. Of course, it has an effect on deck-building as well, as cards that are efficient in more than one concept can save on provision slots which can then be invested elsewhere (as we see in Big Monsters).

Conclusion

This is a deeply complex topic that we could spend days delving into, but for the scope of this series, it is okay simply to scratch the surface. You should now have a better understanding of the Triangle Concept, which may even help you better understand CCGs other than Gwent, as well as how it is applied to Gwent and how we might use it to build better, more efficient decks.

Looking forward, out of an era of Gwent dominated first by decks full of point-slam/control fusion cards, then decks running as few units as possible to counter these decks, it will be interesting to see how the game’s developers attempt to bring the game back into balance, and more interesting for you, we at Aretuza hope, to solve the ever-evolving puzzle caused by the Triangle Concept.

Author

Lothari

Lothari is a long-time fan of CCGs, building up a wealth of experience in Hearthstone, MTG, TESL, Artifact and of course Gwent, which she has been playing since the end of Closed Beta. She always aspires to improve and learn more about what has come to be one of her favourite pass-times. She has also found a passion in creating content for Gwent, and will continue to do so with a passionate and analytical outlook for Team Aretuza. Lothari has a BA in Computing and German and spent four years working as a game developer.